Employment and Social Developments in Europe: 2018 review

16 July 2018by eub2 -- last modified 16 July 2018

This year's edition of the European Commission's yearly Employment and Social Developments in Europe (ESDE) review confirms confirms the ongoing positive labour market trends as well as an improving social situation. The numbers of people in employment reached new record levels. At the same time we witness rising disposable incomes and lower levels of poverty. Severe material deprivation has receded to an all-time low, with 16.1 million fewer people affected, compared with 2012.

Advertisement

What is the focus of the 2018 Employment and Social Developments review?

This year's Employment and Social Developments review focuses on the changing world of work, contributing to research and public debate on the topic of academic research, public authorities and international institutions including the ILO, OECD and the World Bank.

Dedicated chapters in this report examine:

- Main employment and social developments in the EU

- A new labour market with new working conditions: future jobs, skills, and earnings

- Equal opportunities: skills, education and overcoming the disadvantages of socio-economic background and gender

- Inequality of outcomes

- Access and sustainability of social protection in a changing world of work

- Social dialogue for a changing world of work

Why does the 2018 Employment and Social Developments in Europe review focus on the changing world of work?

Globalisation, technological and demographic developments increasingly influence working, living and social conditions. The labour markets have become more dynamic. People work very differently than 15 years ago. Robots, artificial intelligence and digital technologies are revolutionizing the way products are fabricated and services provided. These technologies can make routine tasks in traditional jobs obsolete, raising concerns of job loss. These are key concerns of EU citizens that the Commission addresses through two strands by investing in people's skills through lifelong learning and modernising labour market legislation and social protection systems to respond to the new world of work.

How is the labour market and social situation in the EU developing?

The improving macroeconomic environment has had a positive impact on the labour market. With almost 238 million people in jobs, employment reached new record levels. At the same time, while the number of hours worked per person employed has grown in recent years, they are still below 2008 levels. The unemployment rate stands at 7% in the EU, the lowest rate since August 2008. Long-term unemployment continued to decline, too, but still accounts for nearly half of overall unemployment. The number of unemployed young people (aged 15-24) decreased to 3.37 million, below the pre-crisis (2008) level of 4.2 million. If these positive trends continue, the EU is likely to reach the Europe 2020 target of a 75% employment rate.

Chart 1: EU unemployment rate keeps declining

Source: Eurostat & Commission Forecast

Economic growth also benefited the income situation. Disposable incomes of households in the EU and in a large majority of Member States increased. In 2016 (latest data available), there were 5.6 million fewer people at risk of poverty or social exclusion than at the peak of 2012. The figure has been decreasing year after year, but standing at 117 million people, it is still off the Europe 2020 targets. Severe material deprivation declined in almost all Member States, falling to 33.4 million persons in 2017 (roughly 16.1 million fewer than the peak of 49.4 million in 2012).

Chart 2: Fewer people in severe material deprivation

Source: Eurostat, Commission calculations

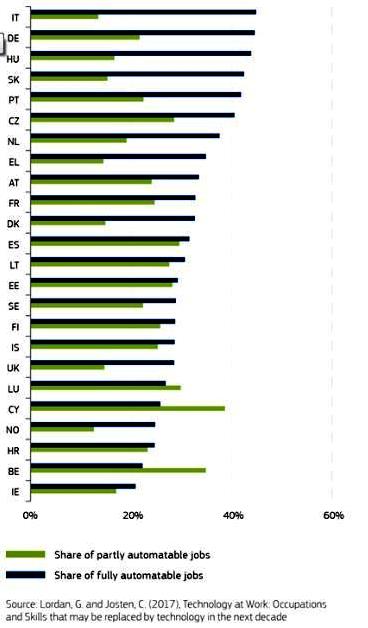

What is the impact of automation on jobs?

While there is no definite conclusion regarding the possible extent of technology's impact on jobs, studies show that repetitive routine tasks are the most prone to full or partial automatisation. This ongoing process is accompanied by job polarisation: the incidence of high- and low-paying jobs has increased, whereas the number of middle income jobs is declining.

Furthermore, certain technological developments have supported the increase in non-standard forms of employment, such as platform work and self-employment. This has brought gains for both businesses and workers, in terms of increased flexibility and a better work-life balance. It has also offered new opportunities to people, including people with disabilities and older people, to enter or remain in the labour market. However, non-standard work may affect working conditions and job quality. The emergence of non-standard work forms has the potential to amplify inequalities, including the gender gap.

In addition, some new forms of work blur the distinction between employment and self-employment, challenging the capacity of European social protection systems to provide adequate coverage to all workers. Distinctions made by the social protection systems need to be rethought in order to provide inclusive protection and ensure long-term sustainability of the social welfare systems. In this light, the Commission has presented in March 2018 a proposal to ensure access to social protection for all workers and the self-employed, including by promoting the transferability of social security rights between jobs and employment statuses.

Technological changes bring about opportunities, too: innovative

technologies increase productivity, create new jobs, facilitate

inclusiveness on the labour market, and allow for more work-life

balance. In light of these developments, education and skills upgrading

play an increasingly important role in helping European workers and

entrepreneurs to adapt. With the Skills Agenda for Europe,

the Commission has prepared the ground to equip people in Europe with

better skills at all levels throughout their lives, and in close

cooperation with Member States, training providers and companies. The

social partners are also adapting to the developments in the labour

market and could play a positive role in adjusting the existing legal

framework to the new forms of work.

Chart 3: State-of-the-art science and technology increases automation in production

Source: Lordan and Josten (2017)

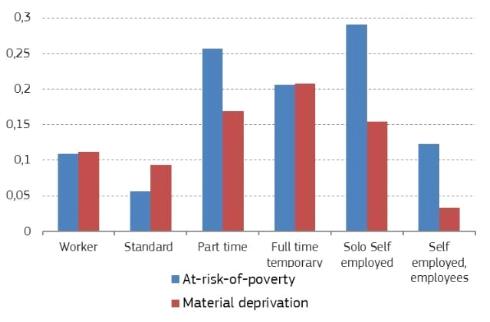

What is the impact of automation on inequalities of income?

Both income level and income inequality depend on hours worked and hourly wages. Therefore the changing world of work can influence incomes to the extent that new forms of work influence either of these factors. Automation impacts the low-skill routine jobs and thereby also the low income-earners. New forms of work often favour non-standard work contracts over standard full-time open ended employment. Non-standard work may increase reliance on certain types of flexible work arrangements, such as solo self-employment and temporary work. This tends to lead to greater income volatility, which could, in turn, increase the vulnerability of workers in non-standard forms of employment. To address this situation, the Commission has proposed a Directive for more transparent and predictable working conditions, including new minimum standards for all workers, also those in non-standard forms of employment.

Chart 4: Risk of poverty by type of contract

Source: EU-SILC, Commission calculations

To what extent will labour be replaced by technology? And is it possible to avoid this?

Automation does not necessarily lead to job destruction. Member States where automation in production is most widespread, for example Germany and the Czech Republic, are also those that are registering the lowest unemployment rates in the EU right now. Germany for example has the highest share of robots in the EU, yet there is little evidence of robots having a negative impact on jobs.

Generally, the extent to which labour can be replaced by technology depends on the level of skills required by the tasks to be performed in each job. This explains the relatively high replacement rate of repetitive low-skill tasks. In contrast, skilled labour is needed to fully exploit the potential of modern technologies by operating, maintaining, repairing, and improving them. Whether or not labour is substituted by technology ultimately depends on the ability of education and training systems to adapt to the fast-changing technological opportunities. This is why it is so important to invest in people's skills, so they remain employable, regardless of the technological evolution.

How do changes such as automation and non-standard forms of work affect the existing social protection systems?

Current social security systems are primarily developed for and geared towards persons working full-time in a long-term relationship with usually one employer. Other groups, such as the self-employed or casual and seasonal workers might be formally excluded from protection coverage. To the extent that the changing world of work increases the number of non-standard work contracts, many will not be covered by social security schemes. This implies growing pressure on the financing base of the social welfare systems, as the contribution base shrinks –an effect which is reinforced by demographic ageing. Future-proof, fit-for purpose social welfare systems would need to deliver life-long key social services, an individualised approach to professional development and employability support.

Do the social partners play a role in managing these changes in the organisation of work?

The social partners at European and national, at cross-industry and sectoral level can help to shape the future of work in a sustainable way. This being said, many new non-standard forms of work are more difficult to organise. The representation of workers' interests in the current, more individualised labour market is increasingly problematic and trade union membership has declined. The representation of employers also stumbles on some new forms of work. In fact, in certain cases it is no longer clear who the employers are. The social partners are already making efforts to adapt to these challenges through:

- up-skilling and re-skilling strategies and actions, such as the set-up of funds to encourage enterprises to facilitate skills development of their employees;

- shaping the increased flexibility in terms of working time and methods made possible by new technology, for instance by supporting the 'right to disconnect';

- maintaining collective bargaining coverage, by finding ways to better include non-standard employment contracts into collective agreements; and

- organising more inclusively the representation of workers' interests in the new labour markets, through targeted campaigns to approach younger workers and workers in the platform economy.

What is Commission doing in order to address the challenges emerging in the context of the changing world of work?

In the context of the European Pillar of Social Rights, the Commission launched several important initiatives, for example:

- a proposal for a Directive on Work-Life Balance, promoting parental, paternity and carer's leave, flexible working arrangements and protection from dismissal and discrimination;

- a proposal for a Directive on transparent and predictable working conditions, complementing and modernising existing obligations to inform workers about working conditions, new rights for all workers, in particular for those in non-standard forms of employment;

- a proposal for a Recommendation on access to social protection, extending access to social protection to non-standard workers and the self-employed.

The Skills Agenda for Europe shows the high priority the Commission places on ensuring that education and training provide people with the knowledge and skills they need to thrive personally, socially and professionally. Each of the 10 actions of the Skills Agenda is now underway. Actions such as the Upskilling Pathways, the Digital Skills and Jobs Coalition and the Blueprint for Sectoral Cooperation on Skills, target up-skilling, cross-sectoral co-operation and identification of future skills needs as well as improving skills intelligence.

The Commission also supports skills development in Europe through EU funds (e.g. the European Structural and Investment Funds, Horizon 2020 and the forthcoming Horizon Europe, the Employment and Social Innovation programme and the "Erasmus+" programme).

The Multiannual Finanical Framework post-2020 will continue to provide financial support. The European Social Fund Plus (ESF+) will be the main EU financial instrument to invest in people, and a key vector to strengthen social cohesion, improve social fairness and increase competitiveness across Europe. The European Globalisation Adjustment Fund (EGF) will be revised so that it can intervene more effectively to support workers who have lost their jobs – focusing on improving the skills and employability of these workers and facilitating the general up-skilling of the European workforce.

Source: European Commission